Sugar Maple

(Acer saccharum)

This impressive tree is best known for being the source of maple syrup and having one of the best

displays of fall color in the forest. The sugar maple’s leaf is the symbol of Canada and is visible on both

the country’s flag and coins. The sugar maple is also the state tree of New York, Vermont, West Virginia,

and Wisconsin. The National Champion Tree resides in Charlemont, Massachusetts. It stands at 112’ tall

with a 19’ diameter and a 91’ spread. These long-lived, slow-growing trees regularly live to be 200 years

old.

This medium to large deciduous tree typically grows 60’ to 80’ height with a 30’ to 50’ spread. The oldest

recorded specimen lives in Pelham, Ontario and is thought to be about 500 years old. The sugar maple is

in the Soapberry family (Sapindaceae) with lychee and soapberry trees. Its common names are hard

maple, sugar tree, and rock maple.

Description

The overall habit of the sugar maple is upright with a dense oval or rounded crown. The leaves are

5-lobed with short pointed or blunt, shallow lobes. The oppositely arranged dark-green, smooth, shiny,

leaves are 4- to 7- inches wide with a slightly shorter length. The leaves are coarsely toothed with fine

white hairs underneath. The stellar fall foliage varies from clear yellow to a fiery orange to red.

The slender, opposite twigs tend to be pale brown or greenish grey. Twigs are densely arranged on the

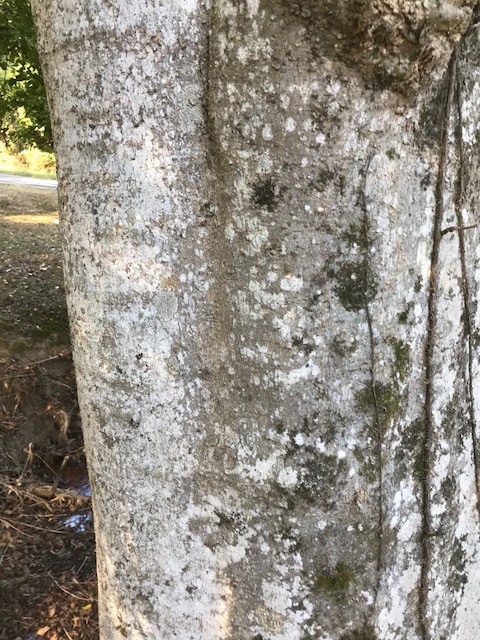

tree and buds are pointed. The dense branches are evenly proportioned about the tree. The bark is

smooth, grey-brown on younger sugar maples becoming furrowed and darker grey as they age. The bark

sometimes becomes plated on older trees. Their shallow and fibrous root systems are not prone to

being invasive.

The flowers are tiny, inconspicuous pale yellow with a light fragrance. They hang from long hairy stalks

in clusters of 8 to 12 flowers. Flowers appear in early spring as the leaves start to expand and create a

yellow fog about the tree when blooming. The fruit is a samara which is a winged nut. It contains one

seed with two wings and can fly like a helicopter. Ash and sycamore trees also exhibit this type of fruit.

Identifying Factors

1) The best identifier for sugar maples is their striking fall color. Depending on the weather, their

fall foliage can range from a brilliant red to tones of yellow and orange.

2) In early spring, their pale-yellow flowers are highly visible in a dormant forest.

3) Sugar maples tend to hold their dead leaves through much of the winter like beech and laurel

oak trees.

4) Once established, sugar maples tend to become the dominate species in that section of forest

where they are growing.

Habitat/Range/Zone

Sugar Maples prefer rich, moist soils. They grow on slopes, upland woods, in valleys, canyons, and along

banks of streams. Sometimes they are found growing on drier rocky hillsides and in ravines. These trees

range from northern Georgia, northward along the Appalachian Mountains through New England into

Novia Scotia, westward to Manitoba, southward through North Dakota into Oklahoma, eastern Kansas,

southern Missouri, and most of Tennessee. Sugar maples tend to be one of the most dominant trees in

their range and are sometimes found in pure stands. They live in Zones 3 to 8.

General Culture

Sugar maples can adapt to many soil types, even tolerating dense clay or alkaline soils. But they prefer

slightly acid, well-drained, moist soils. These trees don’t like dry, sandy soil. They also can’t tolerate

residual highway salt from ice remediation or compacted soils. Therefore, sugar maples don’t make

good median or parking lot trees.

Maples are very shade tolerant, but need at least 6 hours of sun to flourish. Overall, they are low

maintenance trees and can thrive without much attention to mulching, fertilizing, or watering once

established. Plant your tree in the cooler months of spring or fall as a balled & burlaped or container-

grown tree. Use organic soil amendments like ground pine bark, peat moss, or compost when planting.

Mulch them well with 2-4 inches of pine straw or pine nuggets to retain soil moisture and form a weed

barrier. Building a tree well is also recommended to hold more moisture. Irrigate daily for the first two

weeks after planting or if there is a hot/dry spell. The trees can benefit from annual fertilization in early

spring. Also, stressed trees can be aided by root feeding with a liquid fertilizer as needed.

Pruning

Oddly enough, the best time to prune sugar maples is mid-summer. Most other trees should be pruned

in early spring. But, with sugar maples because the sap flow is slower in the warmer months it is better

to shape and train them then. This will help avoid excessive sap bleeding. Wounds will heal faster in July

and August thus making the tree less prone to bacterial or fungal infections. Mature sugar maples don’t

require much heavy pruning. Consistent, regular seasonal pruning when the trees are young will ensure

that the trees form a strong central leader and a well-rounded shape.

Pollination

Sugar maple are wind pollinated although flying insects can play a marginal role. These trees are

monecious or exhibiting both male and female flowers on the same tree. They freely pollinate

themselves as their flowers mature in April and May.

Propagation

There are numerous ways to propagate sugar maples. Most nurseries rely on grafting and budding to

make new trees. Other methods of propagation include cuttings, layering, and seed production.

The easiest form of propagation for sugar maples is by seed. Buy or harvest local seeds for the best

results. Seeds can be collected from October through November after the leaves start changing and

before the seeds start to be dispersed by the wind. Seeds turn a light brown when mature. Test a few

sample seeds for viability. Good, fertilized embryos will be firm while empty unfertilized seeds will easily

be crushed. Cut the clusters of winged seeds from the young twigs at the ends of branches. Seeds don’t

require any cleaning, but the wings can be removed for easier storage. Dry the seeds for 2-4 weeks,

whether saving them for fall planting outdoors or starting cold stratification. The seeds require moist

cold stratification, to mimic the passage of winter, at temperatures at 33 to 40 degrees Fahrenheit for

60 to 90 days. The ideal temperature for germination is 34 degrees F. Use a moist stratification mix

made of 50% peat and 50% sand or vermiculite to maintain seed moisture levels. Plant your seed at ½”

to ¾” deep. Germination should be uniform and germination rates of up to 95% can be expected.

Studies have shown seedlings thrive when grown under 40 to 60% shade their first two years.

Another option is softwood cuttings which can be taken in late spring. Cuttings should be taken in early

morning while twigs are turgid. Take 4- to 6-inch cuttings with 3 nodes present. Place them immediately

in water or in a plastic baggie to minimize water loss. Stick them in trays of a well-drained medium such

as a mixture of 50% finely ground bark or peat moss and 50% coarse sand or perlite. Remove the tips of

cuttings and scrape off a ½-inch section of bark on the base of each cutting for better rooting. Place the

flats in a clear plastic mist tent for moisture control. Mist regularly. If possible, use bottom heat set at

64-75 degrees F. The cuttings should be rooted in 6 to 10 weeks. They can be potted in 1-gallon pots the

following spring and field planted in 2 to 3 years.

In the commercial nursery realm, most new cultivars of sugar maples are made by whip-and-tongue

grafts or bud-grafting. Both require a high degree of dexterity and skill that is better left to professional

propagators.

Pests, Diseases, and General Problems

Though they rarely do any measurable damage. Sugar maples can be fraught with numerous pests such

as pear thrips, bagworms, tent caterpillars, green striped maple worms, leaf rollers, potato leafhoppers,

giant bark aphids, gloomy scale, cottony maple scale, maple shoot borers, and maple petiole borers.

These usually do no more than strip some leaves, produce unsightly honeydew, and damage a few

stems or twigs. Sugar maples are hardy trees and do not normally succumb to attacking pests. Young

trees may benefit from treatments of neem oil or other horticultural oils.

Several leaf spot diseases such as anthracnose can affect these trees but usually do no serious harm. The

only life-threatening disease for sugar maples is verticillium wilt, which is systemic and often fatal.

Sunscald can be a problem to the thin bark of sugar maples, especially to younger trees. To prevent sun

damage to the bark of young trees, wrap the trunks with crepe tree tape. During the hot, dry periods of

summer in the South, leaf scorch or “tatter” can become a problem. Sugar maples are not very drought

tolerant and should not be planted in areas with poor, dry, compacted soil. These trees don’t do well in

most city settings or as median trees because they are sensitive to high sodium in soils coming from de-

icing roads or parking lots. Like silver maples, sugar maples can cause challenges growing turf under

them due to their shallow root systems and dense canopies. Another possible problem with these trees

is their weak branch crotches, like Bradford pears. They may break up during high winds or ice storms.

Harvest & Storage

The Sugaring Season is when sap is collected. This short period normally runs from mid-February to mid-

March, when the night temperatures are below freezing, and the day temperatures are above freezing.

The sap is rising and has the highest sugar content during this period when the trees are breaking

dormancy. It is best to stop harvesting sap before the buds begin to open. The sap will begin to have an

unpleasant flavor and have a lower sugar content. This change in dormancy marks the end of what is

called the Sugaring Season. Mature trees produce between 10 and 20 gallons of sap per season. It takes

about 40 gallons of sap to make 1 gallon of maple syrup.

The collected sap can be concentrated into syrup by boiling the liquid down or by reverse osmosis. It is a

labor-intensive process to boil down the precious sap to make syrup. Usually taking 2 days when done

on a small scale by an individual. The sap is poured into stock pots or metal evaporator pans then

cooked over open fires or propane burners. The darkest, most condensed syrup called amber grade or

dark is the most nutritious. Sycamores trees and other maples such as red maple, silver maple and

boxelder maple can also be tapped for their sap to make sugar or syrup, but sugar maples have the

highest sugar content by far.

Culinary Uses

Maple syrup is a staple kitchen ingredient. It can be used as a condiment on waffles, pancakes, French

toast, or to pour into porridge or oatmeal as a sweetener. It is often used in baking as a sweetener or

flavoring agent.

The maple fruit, samaras, can also be eaten as a snack. First the green samaras are picked, and their

wings removed, then seasoned, roasted, or boiled. Also, young leaves and the inner bark can be foraged.

These can be eaten raw or cooked.

Nutritional Benefits

It is counter intuitive to think using a sweetener like maple syrup, raw honey, or molasses can be good

for you. Maple syrup is a good source of minerals and vitamins. Maple syrup is also full of B vitamins,

especially riboflavin. Maple syrup is high in minerals such as zinc, manganese, calcium, potassium,

copper, magnesium, and iron. Zinc can help improve immunity, especially by slowing the multiplication

of viruses. Whereas, manganese is involved in calcium absorption, blood sugar regulation, and nerve

function. This natural sweetener also has 24 natural antioxidants. These bioactive inflammation-

reducing compounds help protect the immune and nervous systems by reducing free radical damage.

Gallic acid, benzoic acid, and flavanols, such as quercetin or catechin are some of the antioxidants

present in maple syrup. Be sure to purchase dark or B-grade maple syrups, when possible since these

contain more beneficial antioxidants than the lighter grades.

Maple syrup has a lower glycemic index and is lower in calories than raw honey making it a healthier

sweetener choice. Having a low glycemic response makes it good for liver metabolism and maintaining a

favorable intestinal microbiome. Opting for a natural sweetener like maple syrup can help reduce your

intake of refined sugar and artificial sweeteners that cause so many problems like leaky gut syndrome,

irritable bowel syndrome, type 2 diabetes, and heart disease.

Maple syrup is also thought to protect from or slow the growth of colorectal cancer. Research indicates

that maple syrup may protect brain cells from aging and neurodegenerative diseases like ALS and

Alzheimer by lowering nerve inflammation. With its special cocktail of antioxidants, it is supportive of

good reproductive and heart health. Finally, in recent research, maple syrup was found to aid the

efficacy of antibiotics such as ciprofloxacin and carbenicillin.

Native American Uses

Native peoples taught the English and French settlers how to harvest sugar maple sap to make syrup

and sugar. Many tribes such as the Dakota, Cherokee, Iroquis, Chippewa, Menominee, and Ojibwa used

the sap either as a fresh drink or boiled it down into syrup or sugar. The industrious Chippewa traded

the maple sugar to other tribes that didn’t have the prized sugar maples in their area. Many First Nation

people used maple sugar as a seasoning instead of salt. The Potawatomi made a taffy candy for children

as well as letting the sap ferment into a vinegar for cooking. Whereas the Iroquis made a sweet beer by

fermenting the maple sap and bread by mixing ground bark with maple sugar.

Drugs were also made from the inner bark of the sugar maple. Mohegan and Potawatomi made cough

syrup as an expectorant to break up phlegm. The Iroquois concocted an infusion of the inner bark for

eye maladies.

Maple wood was used by the Micmac to make bows and arrows. The Ojibwa employed maple wood for

spoons, paddles, and bowls for cooking. While the Cherokee used maple lumber to make furniture,

structures, and pieces of art.

Ornamental Uses

As one of America’s most-loved trees, the sugar maple is an ideal landscape choice. It is a superior large

ornamental shade tree with an attractive habit, and it exhibits spectacular fall color. It is best suited for

larger sites such as parks, golf courses, and larger residential yards. Sugar maples don’t do particularly

well planted in smaller yards and gardens. Nor do they perform well when planted near streets or

parking lots where they might be exposed to road salts, soil compaction, air pollution, and high heat. It is

also best not to plant them near paved sidewalks, patios, or driveways because of the heaving effect of

their shallow roots.

Other Uses

The sugar maple is one of the most commercially significant hardwoods in North America. The leaves

are used to pack apples and root crops to help preserve them. The wood is highly prized for its

toughness, weight, closed grain, ability to remain smooth when abrased, and its capacity to be highly

polished. This unique wood is especially treasured for the unusual grain patterns known as bird’s eye

maple, fiddle back maple, and curly maple. For this reason, sugar maple is a leading wood used for

furniture, cabinets, flooring, paneling, turnery, and musical instruments. Because the wood also has

good resistance to vibration it is used for tool handles, gunstocks, bowling pins and other sporting

goods. This hard wood holds nails well, is easily glued, and resists shrinkage is also used for ship building

and cutting blocks. The wood is an excellent fuel wood forming extremely hot embers and giving off lots

of heat.

The trees act as mast for songbirds and gamebirds. Many animals such as deer, squirrels, and rabbits like

to feed on the bark and leaves.

Recommended & Related Varieties

Many cultivars of sugar maples for southern climates have been selected over the last several decades

and are available at local nurseries. Some of the better varieties for the South are listed below:

‘Commemoration’ – this variety colors-up in early fall and has good heat tolerance. It has bright red-

orange fall color.

‘Crescendo’ – a cultivar introduced by Morton Arboretum in Illinois. It has good heat and drought

tolerance once established. It has orange red to bright red fall color.

‘Green Mountain’ – dependable in urban settings with good yellow orange to reddish orange fall color.

‘Harvest Moon’ – a selection made in eastern Georgia. It is heat tolerant and has orange fall foliage.

‘Legacy’ – a dependable variety for southern states. Its crown is 50% fuller than other sugar maple

varieties. It has excellent drought resistance and good red to orange-yellow fall color.

Most taxonomist agree there are four other maples species closely related to the sugar maple:

1) Acer barbatum or A. subsp. floridanum (Southern Sugar Maple) is a smaller spreading tree like

the sugar maple found along creeks and in swamps. It has yellow to rust colored fall foliage.

2) Acer grandidentatum (Canyon Maple) is also a smaller tree found in the Rocky Mountains. It has

good tolerance to dry conditions and alkaline soils.

3) Acer leucoderme (Chalkbark Maple) is a small tree with pale gray bark and pubescent leaves.

4) Acer nigrum (Black Maple) is almost identical to sugar maple except its three-lobed leaves curl

downward and is found in hotter, drier areas.

References & Related Links

1) Fredrick, Kate Carter. Miracle-Gro Guide to Growing Stunning Trees & Shrubs. Des Moines, IA:

Meredith Publishing, 2005.

2) Hastings, Don. Trees for the South. Atlanta: Longstreet Press, 2001.

3) Moerman, David E. Native American Ethnobotany. Portland: Timber Press, 1998.

4) Petruzzello, M. 2019. Retrieved October 12, 2021, from

https://www.britannica.com/print/article/571983

5) Sibley, David A. The Sibley Guide to Trees. New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 2009.

6) Stephens, J. 2015. Retrieved October 30, 2022, from

https://site/plantpropatpennstatehrt202/sugarmaple-propagation

7) Sternberg, Guy & Wilson, Jim. Native Trees for North America. Portland: Timber Press, 2004.

8) Toogood, A. American Horticultural Society Plant Propagation. New York: DK Publishing, 1999.

9) Townsend, L & Larson, J. 2020. Retrieved October 28, 2022, from

https://www.uky.edu/ag/entomology/treepestguide/maple.html

10) Tubbs, C. H, Yawney, H.W. & Godman, R.M. 2015. Retrieved August 8, 2022, from

https://www.srs.fs.usda.gov/pubs/misc/ag_654volume_2/acer/saccharum.html

11) Wasowski, S. & Wasowski, A. Gardening with Native Plants of the South. New York: Taylor Trade

Publishing, 1994.

12) Dirr, Michael A. & Heuser, Charles W. Jr. The Reference Manuel of Woody Plant Propagation.

Athens, GA: Varsity Press, 1987.

Suppliers

1) Day Spring Nursery – Rock Island, TN – dayspringnsy@blomand.net

2) Native Forest Nursery – Chatsworth, GA – nativeforestnursery.com

3) Nature Hills Nursery – Omaha, NE – naturehills.com

4) Wilson Brothers Gardens – McDonough, GA – wilsonbrosgardens.com